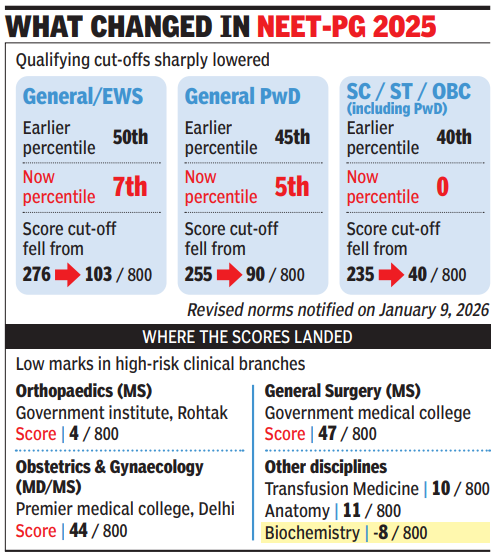

New Delhi: Drastic cuts in NEET-PG eligibility criteria have led to postgraduate medical seats in government universities being filled with extremely low marks, including in high-risk clinical specialties, triggering panic across the medical fraternity, reports Anuja Jaiswal. The impact was evident in the third round of PG counseling, with candidates bagging seats in government medical colleges with scores ranging from single digits to double digits, spanning both clinical and non-clinical subjects. Even top institutions and core clinical branches see seats being allotted to candidates with such scores. A master’s degree in orthopedics at a government institution in Rohtak was allotted to a candidate who scored just 4 out of 800 points, while a seat in obstetrics and gynecology at a senior medical college in Delhi was allotted to a candidate who scored 44 points. General surgery seats were filled with 47 points.

Completely eliminates risk of cut-off patient safety the doctor said

This marks a serious breakdown in medical education and workforce planning,” said a senior faculty member at a government medical college. “Traditionally, orthopedics has been one of the most demanding surgical specialties. Filling it with scores close to zero is not a sign of weaker students but a sign of a system that is under severe stress. “This comes after the Union Health Ministry drastically reduced the eligibility criteria for NEET-PG for the academic session 2025-26, drastically reducing the cutoff for various categories, allowing candidates with extremely low or even negative marks to qualify.

This impact is visible across disciplines. Seats in transfusion medicine are worth 10 marks, anatomy is worth 11 marks and biochemistry is minus 8 marks, many of which fall under reserved and disabled categories. While the revised deadline ensures seats don’t go unfilled, doctors warn the policy risks sacrificing capacity for convenience.“Allowing surgical and clinical departments to be filled with zero or near-zero percentile represents a serious erosion of standards,” said a senior doctor at a government medical college. “A score as low as 4, 11, 44 or 47 out of 800 indicates a lack of basic competency. Removing restrictions entirely would directly jeopardize patient safety.”The current policy marks a sharp shift from the government’s previous stance. In July 2022, the Center had opposed Delhi HC’s plea to lower the NEET-PG cutoff, arguing that the minimum qualifying percentile was crucial to maintain educational standards. The court agreed, warning that lowering standards in medical education could “wreak havoc on society” because medicine involves life-and-death issues.Defending the current framework, a senior health ministry official said PG seats are allotted strictly as per the revised eligibility rules and are aimed at ensuring competency through training and graduation examinations and not just admission threshold. The official said universities are accredited by regulatory bodies and are responsible for unqualified candidates.Medical educators, however, say the trend reflects deeper structural problems — a rapid expansion of seating without a corresponding increase in the pool of trained teachers, overcrowded classrooms and the erosion of bedside skills. “Without strong faculty, rigorous graduation examinations and a system to weed out unsuitable candidates, anyone entering the medical field will end up with a degree,” said a senior academician.Faculty and staff say the consequences are already apparent. Many graduate students arrive without a strong theoretical foundation, clinical skills, or discipline. Pressure on students to pass, weak exit mechanisms and over-reliance on online learning further dilutes the quality of training.“Easy access, even at top institutions, reduces seriousness,” said another doctor who spoke on condition of anonymity. “Numbers are increasing, but the quality of training is declining – which poses long-term risks to patient care.”Doctors warn that the branch of medicine will not immediately reveal its failings. Today, when these physicians practice independently, today’s training gaps may become apparent years from now, with serious implications for patient safety and public trust in the health care system.