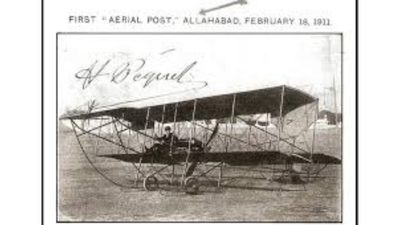

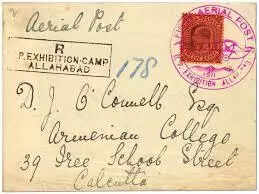

One winter night in 1911, as the sun set over the intersection city of Prayagraj, a small crowd gathered on the riverbank. Yamuna Witness what many thought was nothing more than a spectacle. Kumbh Mela Pilgrims flocked to the city, traders and farmers walked through the UP Showgrounds, and curious onlookers searched for strange contraptions made of wood, fabric and wire. Few realized they were about to witness a moment that would quietly reshape global communications.At around 5:30 pm on February 18, 1911, French pilot Henri Pequet climbed into his Heavyland aircraft, its engines clanging in the evening air. In addition to fuel and instruments, the cockpit contained 6,500 letters – ordinary envelopes entrusted to an extraordinary experiment. When Pekai took off, crossing the Yamuna and turning towards Naini, he took with him not just the mail, but the idea that air could conquer any distance.The flight lasted only 13 minutes. It spans about 15 kilometers from the exhibition ground at Prayagraj to the landing point near Naini Junction (near the present Central Jail). But the brevity of the journey belies its significance.It was the world’s first official airmail service, launched in colonial India at a time when powered flight itself was less than eight years old. According to reports at the time, about a hundred thousand people watched in amazement as the machine rose, crossed the river, and landed safely on the other side.The scene is as symbolic as the event. The UP Fair is an agricultural and industrial fair that brings together innovation and tradition on the banks of the river. The two aircraft were delivered in batches by British officers and assembled in full view, turning the project into drama. This airmail flight was a highlight, but its impact extended far beyond the fairgrounds.More than a century later, the postal service has changed beyond recognition, from fragile biplanes to drones and satellites. However, India’s role in ushering in the age of airmail remains a little-known chapter in the history of aviation and communications.That night in February 1911, among pilgrims, farmers and curious citizens, a modest flight across the Yamuna River quietly sparked a global revolution in how the world conveys information.

Before metal wings, feather wings

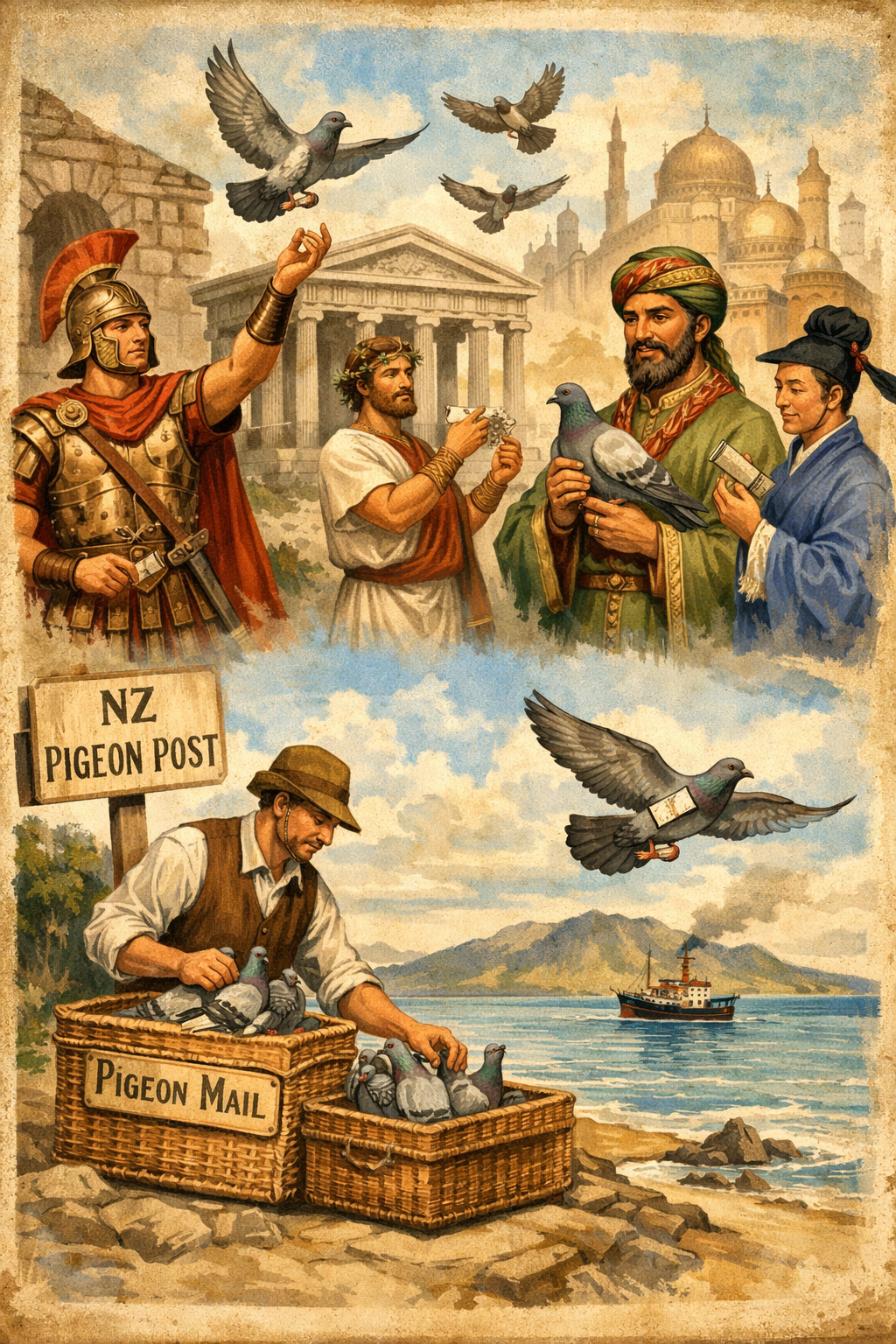

Long before engines roared and wings of fabric and wood rose from the ground, messages were carried by feathers. For at least two thousand years, pigeons have been transporting letters across otherwise difficult, dangerous, or slow distances. A small note will be tied to the bird’s leg and released from a distance, and the trained pigeon will instinctively fly back to its home loft – where the intended recipient awaits.Ancient civilizations relied on this method with great sophistication. The Romans used carrier pigeons to carry military and administrative messages. The Greeks used them to announce the results of sporting events; Persian and Chinese networks also integrated pigeons into their communications systems. In many ways, these birds formed one of the earliest organized long-distance messaging systems.This practice did not disappear with ancient times. A structured postal service based on pigeons briefly operated in New Zealand in the late 19th century. Between 1897 and 1901, New Zealand’s Pigeon Post Office carried messages between the mainland and the Great Barrier Island, issuing stamps that are still popular among stamp collectors today. In an era when reliable telegraph or ferry services were still developing, this was an ingenious solution to geographical isolation.

However, pigeon posts have an inherent limitation that is often overlooked. The bird can only fly home. To send a message from a remote location, someone first has to transport the pigeon there – usually confined to a cage. Even the earliest “airmail” required its own logistics chain.In this context, the leap from pigeon legs to powered flight is not just technical; This is conceptual. When Henri Pequet carried mail across the Yamuna River in 1911, he built on centuries of experiments in conquering distance—this time with machines, not birds, and promised to change the way the nation communicated.

Magenta Mail and the 13-Minute Leap in History

The idea itself was quite bold at the time. According to Postmaster General Krishna Kumar Yadav, Colonel Windham first approached postal authorities with a proposal that sounded more like fantasy than policy: sending mail by airplane. The postmaster general at the time agreed, and preparations began for a landmark communications experiment.Mailbags prepared for flight are deliberately distinctive. It is marked “First Air Mail” and “Uttar Pradesh Exhibition, Allahabad” and features an illustration of an aircraft. The use of magenta ink instead of the usual black ink gives the lot a unique identity.Organizers were acutely aware of the aircraft’s limitations. Weight is a key issue and rigorous calculations are made to ensure the load does not exceed what the machine can lift. Each letter was weighed, restrictions were imposed, and the number of items was ultimately limited to 6,500 items. The flight itself lasted only 13 minutes, but everything that preceded it was planned with military precision.Yadav, who chronicles India’s postal history in his book India Post: 150 Glory Years, points out that the service was not just symbolic; It is also an exceptional quality product. A surcharge of six annas was levied on each letter and the proceeds were donated to the Oxford and Cambridge Hotel in Allahabad. The dormitory became the nerve center of this unusual operation. Pre-order letters were not accepted until noon on February 18, and the crowds were so thick that the building resembled a miniature General Post Office. The Postal Service had to deploy three to four staff members on site to process the mail.Within a few days, nearly 3,000 letters had reached the hotel and were sent onward by air, a testament to the novelty and reputation of the service. Among the senders were the local elite – maharajas, maharajas, princes and prominent citizens of Prayagraj, who were keen to have their names associated with history.One of the envelopes even had a stamp worth Rs 25, a considerable sum at the time, underscoring the symbolic importance of this groundbreaking flight.

From balloon to biplane: the making of Henri Pequet

Henri Pequet’s journey to the banks of the Yamuna was anything but smooth. Born on February 1, 1888, in Braquemont, a small town in the Seine-Bas-Firière region of France, he became interested in flying at a time when aviation was more of an experiment than a profession. In 1905, he began flying hot air balloons under the guidance of Baudry, and later collaborated with the Ville de Paris airship built by Paulham. Learning the basics of aviation in the early years is often accomplished through trial, error, and mechanical improvisation.

In 1908, Pequet worked at the Voisin brothers’ aircraft factory in Mourmelon, one of the pioneer centers of aviation in Europe. His transition from mechanic to pilot was almost accidental. Péquet was on a mission to Chalon to repair an aircraft that had been abandoned due to an Anzani engine failure and received permission to test the aircraft himself. It was there that he first experienced the thrill of controlling an airplane and discovered a talent that would soon define his career.The following year, he was hired as a pilot and mechanic by Chilean aviation entrepreneur José Luis Sánchez. In 1909, Péquet traveled to Johannestal, near Berlin, to attend an aviation conference. Due to circumstances, he replaced another pilot, Edwards, on one flight on the condition that he would no longer be employed as a mechanic. On October 30, he took off for a short but controlled flight and landed successfully. This performance marked his emergence as a professional pilot.Pequet soon returned to the Voisin factory and continued to participate in air shows in Argentina, flying a Voisin biplane powered by a 60-horsepower engine. On March 24, 1910, he made a dramatic flight from Villa Lugano. Later that year, he returned to France and studied at the Voisin Brothers Flying School in Reims, and on June 10, 1910, he was awarded the title of pilot by the French Aero Club with license number 88.Less than a year later, the young French pilot was in colonial India, flying over the Yamuna River and writing a small but immortal chapter in global postal and aviation history.